Sense of smell and scents

Aromas, scents, smells, odors; whatever we might call them are simply airborne molecules of any substance which are sensed by receptors (cells) in the nose.

In addition to aromas, there are odorless chemicals called pheromones which we react to subconsciously through the vomeronasal organ

in the nose. These are chemicals secreted by animals and plants, which trigger social responses in members of the same species,

e.g. marking territory, expressing emotions or mating behaviour.

While their role is crucial in the animal kingdom,

human pheromones have not yet been officially discovered. So, sometimes pheromones are classified alongside aromas too,

even though we can't actually 'smell' them as such.

Physiology

From a physiological point of view, the perception of aromas is rather complex. There are five olfactory organs involved in the process of smell recognition!

The external nose, which we see in the mirror every day, is not directly related to the sense of smell. The main player here is a small section of the olfactory epithelium, an area sensitive cells inside the upper part of the nasal passage which is actually closer to the brain than to the nostrils. Although it only takes in a very small amount of molecules through natural breathing, but they are enough to recognize the aroma.

In some situations where we need more sensory information, we consciously or subconsciously begin to actively sniff; for example, reacting to an unfamiliar, unpleasant or pleasant aroma. But what makes us sniff (when the muscles start working differently) is not yet known for sure. At the moment, it is thought to be something called the Masera's Organ, which is present in animals and children, as well as in about one third of adults. It is believed that it evolved to act like a kind of 'body guard' and causes us to react more actively to certain odors.

Also, on the side of our heads, we humans have what are known as trigeminal nerves which trigger a flight response in reaction to unpleasant smells, e.g. ammonia.

Receptors transmit nerve impulses to the brain, where their signals are processed, resulting in the impression of a smell; either pleasant, unpleasant, alarming, relaxing, intriguing. And we respond accordingly.

How is the impression of an aroma formed?

Although the sense of smell is physiological, the recognition of a smell and the formation of an impression about it depends on several factors. These can be:

- ⚈ psychological

- ⚈ social

- ⚈ cultural

Also, there are many short-term factors including mood, health, hormonal background, smell concentration, relevance of situation, and time of day or year.

At the moment there are two trends in the research of reactions to odors and the impressions created by them:

1. Cultural relativism – how much of our response to aromas is learned “correctly” from society e.g. relatives, friends, teachers etc.

2. Universalism – the extent to which we can understand from birth, which smells are pleasant and which are not, regardless of cultural influence.

Image source: Old Spice

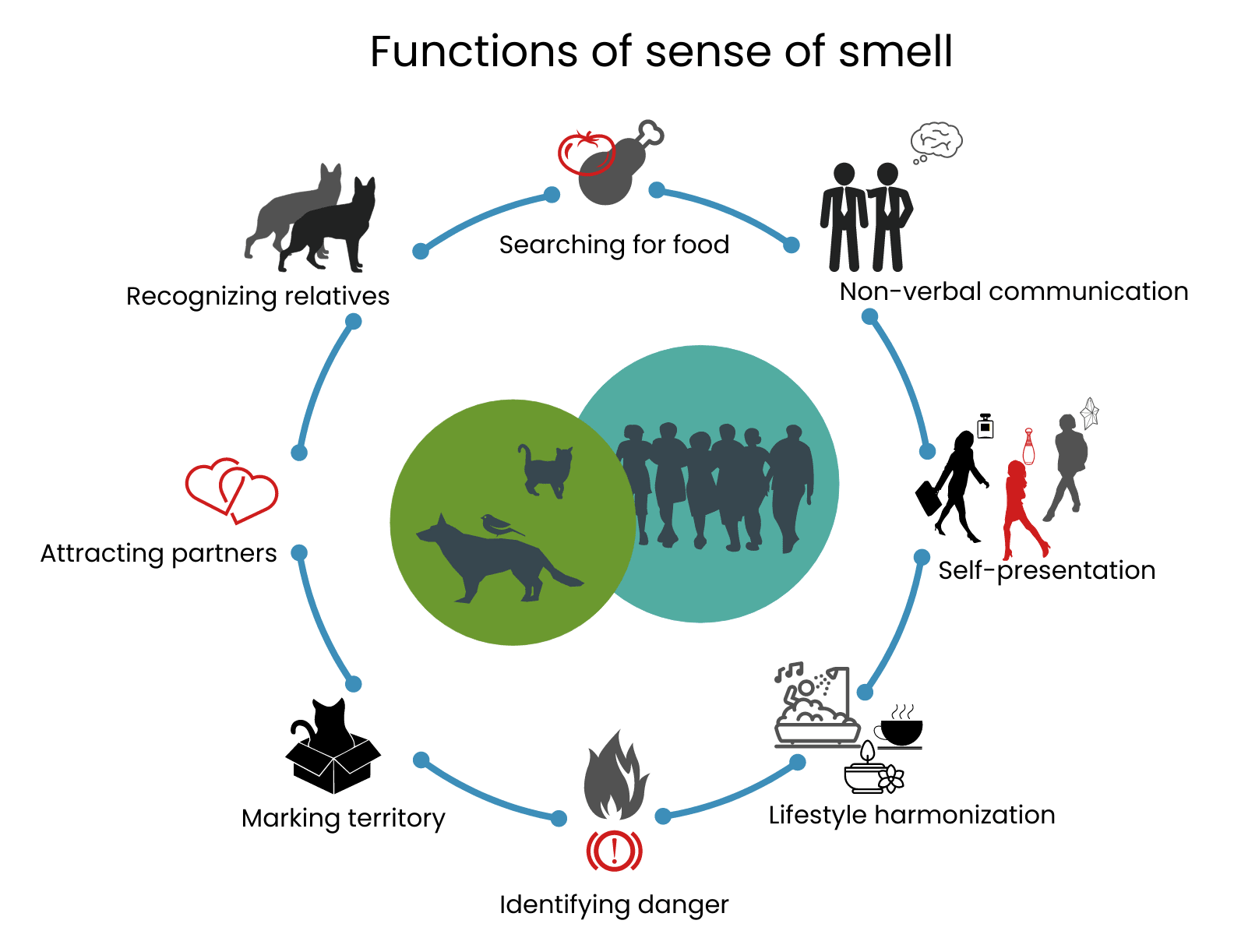

What are the functions of the olfactory system?

The functions of the olfactory system can be divided into two groups; physiological and social. The two are inextricably linked however.

Physiological functions such as the search for food, readiness to reproduce, designation of territory etc. are certainly more important to animals than humans, but socio-cultural functions are essential to humans. Odors can determine the possibilities of communication, form an integral part of people's image, create a festive mood, indicate people's activities, affect their emotions, and have a therapeutic effect under certain conditions.

How important is the sense of smell?

At first glance it may seem like a very poor relation. Up to 90% of the information about the external world we receive through vision, whereas the sense of smell gives us only 2-3 %. Without the sense of smell however, one's perception of the world is greatly diminished. In addition to the previously mentioned functions, the ability to taste food and drink is also dependent on.

The study of aromas and the olfactory system

The sense of smell is undoubtedly the least studied of all the senses. There are probably a few reasons for this, such as the underestimation of the sense of smell in the scientific world, the complexity of collecting and storing samples, difficulties in studying the physiological aspect of perception, and the lack of the necessary technical base.

Despite all the technological progress and development of modern science, the issue of a unified classification of odors has yet to be resolved. Scientists have repeatedly attempted to classify scents over the course of several centuries, but almost none of them cover the entire diversity of the world of scents. Indeed, although aromas literally permeate almost every aspect of our culture, which has developed over thousands of years, almost no attention has been paid by academics to the study of their cultural aspect.

See also:

Consumer culture of scents | The use of scents and getting rid of unpleasant odors